The National Trust wasn't the first to give love, care and affection to West Wycombe Village. Eighty years ago the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) spent time and money preserving cottages and improving quality of life for its tenants. Curator Oonagh Kennedy found a 1933 journal written by the RSA which chronicles their work after buying it from the Dashwood family. I wrote about the parallels Oonagh drew in my last post. But continuing here, she describes how the RSA overspent their budget after buying the village for a mere 7,200 pounds. Bargain!

Nina: Each page of the RSA journal and each document you find including these sale agreement papers appear to have the a much bigger story to tell. Lots of potential and it’s just a small part of a big project, how will you uncover it all?

Oonagh Kennedy: Volunteers can help research and tell the story of West Wycombe Village. I’m recruiting and encouraging volunteers to pick up and run with small projects which can help tell a bigger story. Hopefully some of our research volunteers will pick or find ideas like building materials and their suppliers.

We haven’t covered money, not for the volunteers but for the village and how much it cost the RSA for the 60 lots?

For the 60 lots the RSA paid the Dashwood family a sum in the region of 7,200 pounds.

What a bargain.

But they underestimated how much it would cost to recondition the village and for that they had to take out a further two mortgages which brought the total spend up to 11,200 pounds. This included the purchase and refurbishment work.

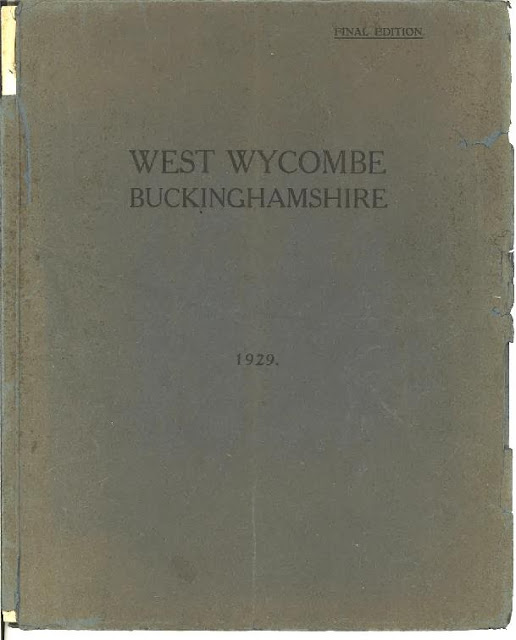

The original sale document of 1929 put the village up as separate lots so an interesting question to me would be why was the village put up for sale in the first place?

What’s the answer?

We haven’t found out. We know that the RSA approached the Dashwood family and that the RSA suggested taking on the village as a village so that they could preserve the character. There seems to have been a very short window of opportunity between the village going up for sale and the RSA purchase. It’s possible that the RSA might have already identified West Wycombe as a very special village.

Just to be clear, the Dashwoods put the village up for sale first before the RSA approach, what’s so interesting about this?

In the sale document which was produced for Sir Dashwood, he actually added a little caveat and said that in purchasing one or two or three lots he wanted to have something like a covenant on the village to “thereby ensure that the character of the buildings facing the main street shall be preserved for the benefit of all concerned.”

Do you think the Dashwoods knew the RSA would approach them before they put the village up for sale?

Not necessarily because I could imagine that if for example it had been sold off in 60 seperate lots, people could have bought it as a business. They could have bought it as public houses or individual cottages which they could’ve either lived in or rented. Had the RSA not stepped in I would imagine in 1929 there could have been people who bought individual properties or businesses. Perhaps the history of how the village evolved would have been quite different.

Could you speculate what it would be like today if the RSA hadn’t bought it?

It’s very hard to say. It would have depended on whether the Dashwood estate maintained an interest so that there would’ve been uniformity in the village for colour presentation and in the painted joinery.

Presumably there have been a lot more development so High Wycombe and West Wycombe could’ve been even closer together than they are now which is pretty close anyway. I think it would be hard to speculate but it certainly wouldn’t have developed necessarily as a village with a central heart. A central character.

|

| Sold by the Dashwood Estate to the Royal Society of Arts in 1929, original documents. |

|

| ….thereby ensure that the character of the buildings facing the main street shall be preserved for the benefit of all concerned. |

N: How does your work here differ from other curatorial jobs? What makes this project unique?

Curating West Wycombe Village is really quite different from the way in which I approach other properties. A curator has to think very carefully about the presentation of a property so that we can safeguard its specialness and its significance. West Wycombe has another step to consider - how to tell the story to the public when the property is a private home like most of the cottages in the village.

When a property is open to the public we try to tell the story to visitors and this can be in the presentation of historic collections to give the public an insight into the specialness and uniqueness of that property.

West Wycombe is different in that I’m being asked to do different things such as researching historical conservation projects, learning about the evolution of the village and how previous members of staff and architects approached conservation issues. I’m additionally thinking about how to share all that information.

An important part of sharing the information is now working with volunteers who are going to collect and collate historical information about West Wycombe. For example we’ll get to know who lived at number 26 over the last 150 years, what were their lives like, how might they have furnished their home, and then what does this tell us about how a village of this kind develops over centuries.

What we really want is to devise a system where anyone who is interested in the village can come along and search to find sequential photographs, a photographic survey of the village over time, or something about the current project. So that if a visitor wants to know more about the RSA’s or National Trust’s work in West Wycombe they can do so.

It’s a goal to share that picture of the village, not just with National Trust staff but also with the volunteers and those who live in the village. Outside of this community there are people with a specialised interest in vernacular buildings who could also use this historical information as a springboard to find out more about the whole village changing over time.

So I’d say that’s the main difference - finding new ways through digital media to share information because it’s highly unlikely that we can open the private homes and doors of West Wycombe Village to the general public. We need to think of new ways of telling that story.